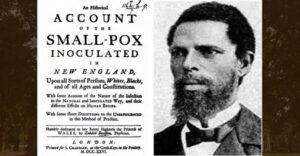

A Slave’s African Medical Science Saves the Lives of Bostonians During the 1721 Smallpox Epidemic By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Correspondent, @StacyBrownMedia

Categories: Articles,

While some may never tire of hearing about the greatness of civil rights leaders, famous black athletes, and renowned entertainers, Black History Month represents a time to focus on the unsung.

In an email, Laurie Endicott Thomas, the author of “No More Measles: The Truth About Vaccines and Your Health,” said the most important person in the history of American medicine was an enslaved African whose real name we do not know.

“His slave name was Onesimus, which means useful in Latin. The Biblical Onesmius ran away from slavery but was persuaded to return to his master,” Thomas said.

“The African-American Onesimus was the person who introduced the practice of immunization against smallpox to North America. This immunization process was called variolation because it involved real smallpox. Variolation led to sharp decreases in the death rate from smallpox and an important decrease in overall death rates,” she said.

This brings us to mind Boston’s own Onesimus.

“While Massachusetts was among the first states to abolish slavery, it was also one of the first to embrace it. In 1720’s Boston, buying a human being was apparently an appropriate way thank to your local man of God.”

“Onesimus was presented to Cotton Mather by his congregation as a gift, which is, of course, extremely troubling,” Brown University history professor Ted Widmer told WGHB.

“Mather was interested in his slave whom he called Onesimus, which was the name of a slave belonging to St. Paul in the Bible,” explained Widmer.

Described by Mather as a “pretty intelligent fellow,” Onesimus had a small scar on his arm, which he explained to Mather was why he had no fear of the era’s single deadliest disease: smallpox.

“Mather was fascinated by what Onesimus knew of inoculation practices back in Africa, where he was from,” said Widmer.

Viewed mainly with suspicion by the few Europeans’ of the era who were even aware of inoculation, its benefits were known at the time in places like China, Turkey and Onesimus’ native West Africa.

Bostonians like Mather were no strangers to smallpox.

Outbreaks in 1690 and 1702 had devastated the colonial city. And Widmer says Mather took a keen interest in Onesimus’ understanding of how the inoculation was done.

“They would take a small amount of a similar disease, sometimes cowpox, and they would open a cut and put a little drop of the disease into the bloodstream,” explained Widmer.

“And they knew that that was a way of developing resistance to it.”

The Harvard University report further cemented what Onesimus accomplished after a smallpox outbreak once again gripped Boston in 1721.

Although inoculation was already common in certain parts of the world by the early 18th century, it was only just beginning to be discussed in England and colonial America, according to researchers.

Mather is largely credited with introducing inoculation to the colonies and doing a great deal to promote the use of this method as standard for smallpox prevention during the 1721 epidemic, Harvard authors wrote.

Then, they noted: Mather is believed to have first learned about inoculation from his West African slave Onesimus, writing, “he told me that he had undergone the operation which had given something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it, adding that was often used in West Africa.’’

After confirming this account with other West African slaves and reading of similar methods being performed in Turkey, Mather became an avid proponent of inoculation.

When the 1721 smallpox epidemic struck Boston, Mather took the opportunity to campaign for the systematic application of inoculation.

What followed was a fierce public debate, but also one of the first widespread and well-documented uses of inoculation to combat such an epidemic in the West.

“A few people who got inoculated did die. But roughly one in 40 did, and roughly one in seven members of the general population dies, so you had a much worse chance of surviving smallpox if you did nothing,” according to WGHB’s research.

Mather and Boylston both wrote about their findings, which were circulated at home and impressed the scientific elite in London, adding invaluable data at a crucial time that helped lay the groundwork for Edward Jenner’s famed first smallpox vaccine 75 years later.

The scourge of slavery would continue in Massachusetts for another 60 years, but as for the man whose knowledge sparked the breakthrough,

“Onesimus was recognized as the savior of many Bostonians, admired, and then emancipated,” Widmer said. “Onesimus was a hero. He gave of his knowledge freely and was himself freed.”